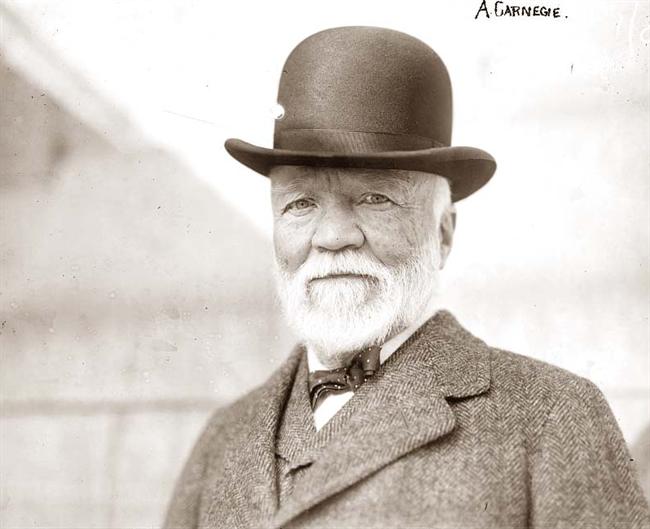

Carnegie – Dunfermline’s Homeboy

Whether you pronounce it Carr-niggy (like the Yanks) or Carn-egg-ghee (with equal accent on all three syllables as it is locally) most people know at least a little bit about Andrew Carnegie, Dunfermline’s “Most Famous Son”. What may not be as well-known is how connected he stayed to his local roots and how his generosity still contributes to the daily lives of all those who live in Dunfermline.

Andrew Carnegie was born here in Dunfermline in a typical weavers cottage to William Carnegie and Margaret Morrison (mother’s maiden name is important so please take note).Below is the actual room in which he was born. His brother and parents would live, cook, play and sleep in this space, and his mother would wind bobbins to drop through the floor to where her husband worked in the main room below. To the right of the open door is a double bed that fills the remainder of the room.

Snug ‘eh? And I think my kids are always underfoot in the winter!

His father worked in this room on a hand-loom, weaving Damask Linen for which Dunfermline was famed in the early 19th century. In addition to weaving, both his father’s and mother’s families were very involved in radical political views including; campaigning for a parliamentary electoral system, Catholic emancipation and even had family that had participation in the “Meal Riots” of the 1770s that swept Europe.

The life of a weaver and his family would not have been and easy one, and would have been a noisy, cramped and exhausting existence. Now for all my affection for the place, when you say to someone that you live in Dunfermline – even today – you are not automatically met with the sharp intake of breath and the narrowing of the eyes that would signal the thought, “oh, you lucky devil” in the mind of your conversant. Back in young Carnegie’s day I could only imagine how challenging (and cold) it would have been.

To add insult to injury, right next door to the cottage sits 76 acres of the most glorious cultivated landscape known as Pittencreiff Park and The Glen. In Carnegie’s’ youth the grounds of the property included the Palace at Dunfermline (another story for another day) and Dunfermline Abbey, as well as the land known as Pittencrieff Estate and Glen.

Like most private estates the land was not open to the public, but the fact that it also had encroached onto land that had been monastic and now excluded people from the additional sites that were considered national treasures was too much for some. Carnegie’s uncle Tom “Bailie” Morrison eventually applied for a court order to grant access to the public – for one day a year – and was successful. However in doing so, he so enraged the Laird of Pittencrieff, Colonel James Hunt, that he too secured a court order that no Morrison was EVER to be allowed onto his estate. Thus, Carnegie as the nephew of a Morrison was legally and permanently banned from the grounds.

By 1848, the rise of industrial looms and worsening economic times in Scotland saw the Carnegie family heading off for better fortune in America, specifically Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. From this point Carnegie’s story is more well-known. The “rags to riches” story of a young immigrant who worked his way up from bobbin boy to telegraph operator, and eventually becoming synonymous with steel, railroads and a “Captain of Industry” of the newly industrial America. Even though his wealth was garnered not without some grave controversy, such as the Homestead strikes of 1892, his philanthropic works were becoming legendary.

Not too Shabby, Skibo Castle stayed in the Carnegie Family until 1982. Now a Super Posh Private Golf Club and Can be Hired for Weddings like Madonna & Guy Rithche

In 1895, as a surprise 60th birthday present, Carnegie’s wife purchased the original Carnegie cottage in Dunfermline. (What to get for the man with everything ?) Perhaps it was being able to revisit his physical origins, or maybe it was something that burned in him deeper and longer, that even though he could afford (amongst his many other residences) his Scottish summer retreat of Skibo Castle,

the thing he craved to own above all else was this – the key to Pittencreiff Estate – from which he was STILL banned.

FINALLY, in 1902 Carnegie purchased Pittencreiff Estate and Glen, with the express intent of turning it over to the people of Dunfermline, so “that the toiling mases may know sweetness and light”. He did retain actual ownership of the Tower House as with it came the inherited title of “Laird of Pittencreiff”, and so at 67 years of age he took his first stroll amongst the grounds he had been denied entrance in his youth.

True to his word, in 1903 a caretaker was installed and the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust was created to manage and maintain the cottage, and the former estate for the public. In Carnegie’s own words, “No gift I have made or ever can make can possibly approach that of Pittencrieff Glen”, also adding it as “the most soul-satisfying public gift I ever made or ever can make – to the people of Dunfermline”. Now, I read this on plaque in the park on one my first visits and recall thinking – oh isn’t that nice. Now that I understand a bit more about his back story I realise that this gift must have meant so very much more to him. Pittencreiff Park is deserving of its own entry so I will wrap it up by pointing out that in addition to giving Dunfermline one of its greatest resources of “The Glen” as it is now know locally, Carnegie also provided for a free public library, public swimming baths and a wide variety of other great additions to his hometown

A few additions to the Glen came after his death in 1919, all at the instruction of his wife Louise. She commissioned the impressive iron gates that mark the entrance to Pittencreiff Park at the bottom of Dunfermline’s High Street, and also the Birthplace Museum now connected to the original weavers cottage.

Admission is free and there is still loads to see (I didn’t give it all away), so it is well worth a trip.

PS This is not an advertisement, just me having a blether.

![Carnegie-Andrew[1]](https://i0.wp.com/albaliving.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Carnegie-Andrew1-300x244.jpg?resize=300%2C244)

![5683[1]](https://i0.wp.com/albaliving.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/56831.jpg?resize=200%2C200)

![800px-Louise_Carnegie_Gates,_Pittencrieff_Park[1]](https://i0.wp.com/albaliving.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/800px-Louise_Carnegie_Gates_Pittencrieff_Park1-300x225.jpg?resize=300%2C225)

love this, very interesting! good scoops.

and when i worked at a Carnegie institution in NYC, my friends were so excited to finally learn how the name is pronounced…but even there they did it both ways! alas…